Diane Arbus photograph

Exhibition: ‘Portraits of New York: Photographs from the MoMA’ at La Casa Encendida, Madrid

Exhibition dates: 27th March – 14th June, 2009

I have collected a few photographs that appear in the exhibition.

“Photographs from the MoMA, which will provide an in-depth look at an essential component of the MoMA’s assets: its photography collection. Curated by Sarah Hermanson Meister, associate curator of the museum’s department of photography, the exhibition offers an overview of the history of photography through the work of over 90 artists, with the iconic city as a backdrop. It includes some of the most prestigious names in photography, such as Berenice Abbott, Diane Arbus, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walter Evans, Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, Cindy Sherman, Irving Penn and Alfred Stieglitz.

Paul Strand

‘Wall Street’

1915

Ted Croner

‘Central Park South’

1947-48

For Sarah Hermanson Meister, associate curator of the MoMA’s Department of Photography, “Portraits of New York amply reflects the history of synergies of this medium and of the Big Apple during a period of important transformations for both. The photographs generated by the restless and constant commitment of numerous photographers to the city of New York have played a fundamental role in determining how New Yorkers perceive the city and themselves. These photographs have also defined the city’s image in the world’s imagination.

[…] The urban landscape of the city is a combination of the old and the new in constant evolution, and these physical transformations are repeated in the demographic changes that have characterised the city since the 1880s, when massive waves of immigrants began to arrive. This same diversity can be seen in the photography of New York of the past four decades. Just as its architects are inspired and limited by surrounding structures and building codes, and just as its inhabitants learn and rub up against each other and previous generations, so too the photographers of New York transport the visual memory of a an extensive and extraordinary repertoire of images of the city. They take on the challenge of creating new works that go beyond traditions and respond to what is new in New York.

Bernice Abbott

‘Nightview, New York City’

1932

The exhibition curator continues: “Throughout the 20th century, numerous artists have felt inspired by New York’s combination of glamour and rawness. The city – which acquired its modernity at the same pace as photography, and in an equally impetuous and undisciplined way – has always been a theme of particular vitality for photographers, both those who have visited the city and those who live in it. On one occasion, faced with the challenge of capturing the essence of New York with a camera, the photographer Berenice Abbott wondered, “How shall the two-dimensional print in black and white suggest the flux of activity of the metropolis, the interaction of human beings and solid architectural constructions, all impinging upon each other in time?” Each of the photographs reproduced here is a unique response to that question.

Arthur (Weegee) Fellig

‘Coney Island’

1940

Diane Arbus

‘Woman with Veil on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C’

1968

New York may not be the capital of the United States, but it prides itself on being the capital of the world. Its inhabitants are intimate strangers, its avenues are constantly teeming and its buildings are absolutely unmistakeable, though they are packed so close together that it is impossible to see just one. The New York subway runs twenty-four hours a day, which has earned it the sobriquet of “the city that never sleeps.” It is the model for Gotham City, the disturbing metropolis that Batman calls home, and a symbol of independence and a wellspring of opportunities in a wide variety of films, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Working Girl. And this is just a sample of the captivating and abundant raw material that the city offers to artists, regardless of the medium in which they work. However, it is the convergence of photographers in this city – in this place that combines anonymity and community, with its local flavour and global ambitions – that has created the ideal setting for the development of modern photography.”

Text from the La Casa Encendida website

Bruce Davidson

‘Untitled’ from the ‘Brooklyn Band’ series

1959

Cindy Sherman

‘Untitled Film Still #21′

1978

La Casa Encendida

Ronda Valencia, 2 28012 Madrid

La Casa Encendida is open from Monday to Sunday from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day of the year except national and Community of Madrid holidays.

Posted in American, american photographers, black and white photography, Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus, documentary photography, exhibition, gallery website, New York, photography, street photography Tagged: Arthur Fellig, Bernice Abbott Nightview New York City 1932, Bruce Davidson, Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus Woman with Veil on Fifth Avenue 1968, exhibition, La Casa Encendida, madrid, New York, Paul Strand Wall Street 1915, Portraits of New York: Photographs from the MoMA, Ted Croner Central Park South 1947, the metropolitan museum of modern art, Weegee Coney Island 1940

Exhibition: ‘Diane Arbus’ at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Exhibition dates: 9th May – 31st August, 2009

“A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.”

Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus

‘Tattooed Man at a Carnival, Md.,’

1970

I have collected some photographs from the exhibition mainly from the ‘Box of Ten’ 1971 that features in the show.

Diane Arbus is one of my favourite photographs – how I would love to see this show!

Marcus

“One of National Museum Cardiff’s main art exhibitions in 2009 reveals the work of legendary New York photographer Diane Arbus (1923 -1971), who transformed the art of photography. ‘Diane Arbus’, which comprises 69 black and white photographs including the rare and important portfolio of ten vintage prints: ‘Box of Ten’, 1971, is one of the best collections of Arbus’s work in existence. A large selection of these images will be on display at the Museum from 9 May until 31 August 2009.

Capturing 1950s and 1960s America, Arbus is renowned for portraits of people who were then classed on the outskirts of society nudists, transvestites, circus performers and zealots. In one of her most famous works, ‘Identical Twins, Roselle, NJ’ of 1967, the twins are photographed as if joined at the shoulder and hip with only three arms between them.

Her powerful, sometimes controversial, images often frame the familiar as strange and the strange or exotic as familiar. This singular vision and her ability to engage in such an uncompromising way with her subjects has made Arbus one of the most important and influential photographers of the twentieth century.

This singular vision and her ability to engage in such an uncompromising way with her subjects has made Arbus one of the most important and influential photographers of the twentieth century.”

Text from the National Museum of Cardiff website

Diane Arbus

‘A young man with curlers at home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C.,’

1966

Diane Arbus

‘A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y.,’

1968

Diane Arbus

‘A Jewish Giant at home with his parents’

1967

“From 1969 to 1971 Arbus was absorbed in the creation of a limited edition portfolio, A box of ten photographs. The portfolio was intended to present her work as an artist in the manner of the special print editions offered by new artists’ presses such as Crown Point and Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE). This group of pictures and its presentation was a very conscious statement of what she stood for, and how she regarded her own photography. The pictures range from the relatively early ones of the Nudists in their summer home and Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I., both of 1963; through the now iconic Identical twins, Roselle, N.J., 1967 and Westchester Couple sunning themselves on their lawn, to the later pictures of the Jewish giant, the Mexican Dwarf in his hotel room, N.Y.C. and the King and Queen of a senior citizens’ dance, N.Y.C., all of 1970. There is clearly an attempt to be representative of the general idea, the larger plan behind her work. There is also a significant stylistic range, from the graceful daylight in the picture of the older couple in the nudist camp, to the later picture of the elderly king and queen, whom she photographed with sharp flash. She included Xmas tree, a work without human subjects. The prints for this portfolio were selected three years after the New Documents exhibition, before there was thought of another show. But the pictures constituted a kind of exhibition in and of themselves, to be examined one at a time, rather than all at once. From her letters, we know that the idea of a clear box was very important; it was to serve as both a container and a display case allowing the owner to reorder and display the pictures easily. Just as she had wanted the black border of the print to show in the New Documents exhibition, here she wished to exhibit the entire print as it appeared on the photographic paper …

Diane Arbus

‘Mexican Dwarf in his hotel room, N.Y.C.,’

1970

Diane Arbus

‘Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I.,’

1963

Most of the pictures in the portfolio either depict families or refer to the family. Even the corner of the cellophane-looking room in Levittown is made by peering over the two outstretched arms of a family armchair, posed like the trousered knees of the empty chair in the picture of the Jewish giant. The idea of the family album was a private but expressive metaphor for her. As in a family album, each member is part of the larger group; they are related, perhaps even tolerated, and harmony may be rare and perhaps even uninteresting. But they are all considered with the same intelligent and human regard. She photographed the Jewish giant as a mythic figure, enclosed in a modest Bronx living room, an unconventional member of an otherwise conventional family: ‘I know a Jewish giant who lives in Washington Heights or the Bronx with his little parents. He is tragic with a curious bitter somewhat stupid wit. The parents are orthodox and repressive and classic and disapprove of his carnival career…They are truly a metaphorical family. When he stands with his arms around each he looks like he would gladly crush them. They fight terribly in an utterly typical fashion which seems only exaggerated by their tragedy… Arrogant, anguished, even silly.’“

Sandra S. Phillips, senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from the book Diane Arbus Revelations.1

Diane Arbus

‘Identical twins, Roselle, N.J.,’

1967

Diane Arbus

‘King and Queen of a senior citizens’ dance, N.Y.C.,’

1970

1. Phillips, Sandra. “The Question of Belief,” in Diane Arbus Revelations. London: Random House, 2003, pp. 66-67.

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP

Opening hours: Tues – Sunday, 10 – 5pm

National Museum of Wales website

Posted in American, american photographers, black and white photography, Diane Arbus, documentary photography, exhibition, existence, gallery website, memory, photography, portrait, reality Tagged: A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, A Jewish Giant at home with his parents, a young man iwht curlers at home on West 20th Street, Box of Ten photographs 1971, Diane Arbus, exhibition, King and Queen of a senior citizens dance, Mexican Dwarf in his hotel room, National Museum of Wales, tattooed man at a carnival, Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown

Exhibition: ‘Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus: A Printed Retrospective, 1960-1971′ at the Modern Museum, Malmo

Exhibition dates: 27th March – 1st August 2010

.

Many thankx to the Modern Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

.

.

.

Picture Magazine #16

Diane Arbus: A Monograph of Seventeen Photographs

1964

.

.

Diane Arbus

Magazine spread featuring ‘Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I.,’ 1963 and ‘A Young Brooklyn Family Going for a Sunday Outing, N.Y.C.’ 1966 (see either installation photograph below and enlarge to see pairing on the back wall!)

.

.

Diane Arbus

Magazine spread featuring ‘Mexican Dwarf in his hotel room, N.Y.C.,’ 1970 and ‘Identical twins, Roselle, N.J.,’

1967 (see either installation photograph below and enlarge to see pairing on the back wall!)

.

.

Diane Arbus

The New Life

Harper’s Bazaar (February, 1968)

Copyright © 1968 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

.

.

“The exhibition Pierre Leguillon features “Diane Arbus: a printed retrospective, 1960 – 1971″ presents approximately one hundred Diane Arbus photographs for magazines. According to its author, Pierre Leguillon, the aim of the small book that accompanies the exhibition is not to interpret the images or items on display but “simply to replace the photographs in the context of their initial appearance.” The aim of this conversation is in turn to replace this project in the context of Leguillon’s artistic practice.

About the title, Leguillon explains “it is analogous to the term one would use for an exhibition featuring all of Goya’s printwork. Showing everything that appeared in magazines during Diane Arbus’s lifetime participates in the same gesture. It’s also a matter of exposing the working process that shapes the exhibition. The poster created by Philippe Millot from one of my photos plays an important role in this. What we see is the pile of collected magazines that makes up the retrospective, with its somewhat vain and fanciful side, but we also see a sculpture or a monument. […] I wanted to show the pictures that were actually published that differ from some exhibition prints and also to show how they were published. It started from the observation that these photos were printed well in perfect layouts in sixties magazines. So I’m using the page layout as a ‘prefabricated’ exhibition structure: the mats are already there, along with picture titles and artist signature. So I don’t have to add descriptive labels.” (Interview/Pierre Leguillon – “not to be missed”: Diane Arbus, in: Particules no 22 – December 2008/January 2009) …

The French artist Pierre Leguillon has compiled a unique retrospective on the large body of work produced by Diane Arbus for the Anglo-American press in the 1960s. This spring and summer, the exhibition is being shown at Moderna Museet Malmö, featuring some 100 photos in their original context – on the pages of magazines.

In the 1960s, Diane Arbus (1923-1971) was used widely by publications such as Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, Nova and The Sunday Times Magazine. Her extensive work for the Anglo-American press is relatively unknown, however, and Pierre Leguillon’s presentation is the first time it has been shown in this way: a printed retrospective in the form of some one hundred original magazine spreads.

The exhibition presents a broad material comprising hundreds of photos that demonstrate her wide variety of subjects and genres: photo journalism, celebrity shots, kids’ fashion and several photo essays. All Arbus’ photos are shown in their original social and political context, in the pages of original magazines. The images are shown as they were intended to be seen, in their intended format and setting and in relation to a text. Interspersed in this rich array of Arbus’ photographic output are various texts and images by other photographers (Walker Evans, Annie Leibovitz, Victor Burgin, Wolfgang Tillmans, Matthieu Laurette, Bill Owens) directly or indirectly referring to a specific part of Arbus’ oeuvre and thus emphasising its strong impact on her contemporary times and the present day.

The retrospective, which was put together by the French artist Pierre Leguillon and is presented as a work of art/exhibition/collection, also encourages us to reflect on these aspects and on the relationship between the original and the copy.

Press release from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

A short conversation with Pierre Leguillon

.

.

Diane Arbus

Make War Not Love!

Sunday Times Magazine (London) (September 14, 1969)

Copyright © 1969 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

.

.

Diane Arbus

The Vertical Journey: Six Movements of a Moment within the Heart of the City

Esquire (July, 1960)

Copyright © 1968 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

.

.

Pierre Leguillon

Installation view: Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus: A Printed Retrospective, 1960-1971, Moderna Museet Malmö, 27 March-1 August 2010. Collection Kadist Art Foundation. Photo: Prallan Allsten

© Moderna Museet

.

.

Pierre Leguillon

Installation view: Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus: A Printed Retrospective, 1960-1971, Moderna Museet Malmö, 27 March-1 August 2010. Collection Kadist Art Foundation. Photo: Prallan Allsten

© Moderna Museet

.

.

Moderna Museet Malmö

Gasverksgatan 22 in Malmö

Moderna Museet Malmö is located in the city centre of Malmö. Ten minutes walk from the Central station, five minutes walk from Gustav Adolfs torg and Stortorget.

Opening hours:

Tuesday, Thursday - Sunday 11-18

Wednesday 11-21

Mondays closed

Moderna Museet Malmö website

Filed under: american photographers, black and white photography, Diane Arbus, documentary photography, exhibition, gallery website, installation art, photographic series, photography, photojournalism, portrait, surrealism Tagged: Diane Arbus Esquire, Diane Arbus Harper's Bazaar, Diane Arbus Make War Not Love!, Diane Arbus Sunday Times Magazine, Diane Arbus The New Life, Diane Arbus The Vertical Journey: Six Movements of a Moment within the Heart of the City, Diane Arbus: A Monograph of Seventeen Photographs, Make War Not Love!, Moderna Museet Malmö, Picture Magazine #16, Picture Magazine #16 Diane Arbus: A Monograph of Seventeen Photographs, Pierre Leguillon, Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus, Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus: A Printed Retrospective, The New Life, The New Life Harper's Bazaar, The Vertical Journey, The Vertical Journey: Six Movements of a Moment within the Heart of the City

Review: ‘American Dreams: 20th century photography from George Eastman House’ at Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria

Exhibition dates: 16th April – 10th July 2011

.

Many thankx to Tansy Curtin, Senior Curator, Programs and Access at Bendigo Art Gallery for her time and knowledge when I visited the gallery; and to Bendigo Art Gallery for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

.

.

.

Gertrude Käsebier

The Sketch (Beatrice Baxter)

1903

platinum print

Gift of Hermine Turner

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

Dorothea Lange

Kern County California

1938

gelatin silver print

Exchange with Roy Stryker

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

Ansel Adams

Winter Storm

1942

.

.

Diane Arbus

Untitled (6)

1971

.

.

This is a fabulous survey exhibition of the great artists of 20th century American photography, a rare chance in Australia to see such a large selection of vintage prints from some of the masters of photography. If you have a real interest in the history of photography you must see this exhibition, showing as it is just a short hour and a half drive (or train ride) from Melbourne at Bendigo Art Gallery.

I talked with the curator, Tansy Curtin, and asked her about the exhibition’s gestation. This is the first time an exhibition from the George Eastman House has come to Australia and the exhibition was 3-4 years in the making. Tansy went to George Eastman House in March last year to select the prints; this was achieved by going through solander box after solander box of vintage prints and seeing what was there, what was available and then making work sheets for the exhibition – what a glorious experience this would have been, undoing box after box to reveal these magical prints!

The themes for the exhibition were already in the history of photography and Tansy has chosen almost exclusively vintage prints that tell a narrative story, that make that story accessible to people who know little of the history of photography. With that information in mind the exhibition is divided into the following sections:

Photography becomes art; The photograph as social document; Photographing America’s monuments; Abstraction and experimentation; Photojournalism and war photography; Fashion and celebrity portraiture; Capturing the everyday; Photography in colour; Social and environmental conscience; and The contemporary narrative.

.

There are some impressive, jewel-like contact prints in the exhibition. One must remember that, for most of the photographers working after 1940, exposure, developing and printing using Ansel Adams Zone System (where the tonal range of the negative and print can be divided into 11 different ‘zones’ from 0 for absolute black and to 10 for absolute white) was the height of technical sophistication and aesthetic choice, equal to the best gaming graphics from today’s age. It was a system that I used in my black and white film development and printing. Film development using a Pyrogallol staining developer (the infamous ‘pyro’, a developer I tried to master without success in a few trial batches of film) was also technically difficult but the ability of this developer to obtain a greater dynamic range of zones in the film itself was outstanding.

“The Zone System provides photographers with a systematic method of precisely defining the relationship between the way they visualize the photographic subject and the final results… An expressive image involves the arrangement and rendering of various scene elements according to photographer’s desire. Achieving the desired image involves image management (placement of the camera, choice of lens, and possibly the use of camera movements) and control of image values. The Zone System is concerned with control of image values, ensuring that light and dark values are rendered as desired. Anticipation of the final result before making the exposure is known as visualization.”1

Previsualisation, the ability of the photographer to see ‘in the mind’s eye’ the outcome of the photograph (the final print) before even looking through the camera lens to take the photograph, was an important skill for most of these photographers. This skill has important implications for today’s photographers, should they choose to develop this aspect of looking: not as a mechanistic system but as a meditation on the possibilities of each part of the process, the outcome being an expressive print.

.

A selection of the best photographs in the exhibition could include,

1. An original 1923 Alfred Steiglitz Equivalent contact print - small (approx 9cm x 12cm, see below), intense, the opaque brown blacks really strong, the sun shining brightly through the velvety clouds. In the Equivalents series the photograph was purely abstract, standing as a metaphor for another state of being, in this case music. A wonderful melding of the technical and the aesthetic the Equivalents’ “are generally recognized as the first photographs intended to free the subject matter from literal interpretation, and, as such, are some of the first completely abstract photographic works of art.”2

2. Paul Strand Blind (1915, printed 1945) – printed so dark that you cannot see the creases in the coat of the blind woman with a Zone 3 dark skin tone.

3. Lewis Hine [Powerhouse mechanic] see below, vintage 1920 print full of subtle tones. Usually when viewing reproductions of this image it is either cropped or the emphasis is on the body of the mechanic; in this print his skin tones are translucent, silvery and the emphasis is on the man in unison with the machine. The light is from the top right of the print and falls not on him directly, but on the machinery at upper right = this is the emotional heart of this image!

4. Three tiny vintage Tina Modotti prints from c. 1929 – so small, such intense visions. I have never seen one original Modotti before so to see three was just sensational.

5. Walker Evans View of Morgantown, West Virginia vintage 1935 print – a cubist dissection of space and the image plane with two-point perspective of telegraph pole with lines.

6. An Edward S. Curtis photogravure Washo Baskets (1924, from the portfolio The North American Indian) – such a sumptuous composition and the tones…

7. Ansel Adams 8″ x 10″ contact print of Winter Storm (1944, printed 1959, see above) where the blackness of the mountain on the left hand side of the print was almost impenetrable and, because of the large format negative, the snow on the rock in mid-distance was like a sprinkling of icing sugar on a cake it was that sharp.

8. A most splendid print of the Chrysler Building (vintage 1930 print, approx. 48 x 34 cm) by Margaret Bourke-White – tonally rich browns, smoky, hazy city at top; almost like a platinum print rather than a silver gelatin photograph. The bottom left of the print was SO dark but you could still see into the shadows just to see the buildings.

9. An original Robert Capa 1944 photograph from the Omaha Beach D Day landings !!

10. Frontline soldier with canteen, Saipan (1944, vintage print) by W Eugene Smith where the faces of the soldiers were almost Zone 2-3 and there was nothing in the print above zone 5 (mid-grey) – no physical and metaphoric light.

11. One of the absolute highlights: two vintage Edward Weston side by side, the form of one echoing the form of the other; Nude from the 50th Anniversary Portfolio 1902 – 1952 (1936, printed 1951), an 8″ x 10″ contact print side by side with an 8″ x 10″ contact print of Pepper No. 30 (vintage 1930 print). Nothing over zone 7 in the skin tones of the nude, no specular highlights; the sensuality in the pepper just stunning – one of my favourite prints of the day – look at the tones, look at the light!

12. Three vintage Aaron Siskind (one of my favourite photographers) including two early prints from 1938 – wow. Absolutely stunning.

13. Harry Callahan. That oh so famous image of Eleanor and Barbara, Chicago (vintage 1953 print) that reminds me of the work of Jeffrey Smart (or is it the other way around). The wonderful space around the figures, the beautiful composition, the cobblestones and the light – just ravishing.

14. The absolute highlight: Three vintage Diane Arbus prints in a row – including a 15″ square image from the last series of work Untitled (6) (vintage 1971 print, see above) – the year in which she committed suicide. This had to be the moment of the day for me. This has always been one of my favourite photographs ever and it did not disappoint; there was a darkness to the trees behind the three figures and much darker grass (zone 3-4) than I had ever imagined with a luminous central figure. The joyousness of the figures was incredible. The present on the ground at the right hand side was a reveleation – usually lost in reproductions this stood out from the grass like you wouldn’t believe in the print. Being an emotional person I am not afraid to admit it, I burst into tears…

15. And finally another special…. Two vintage Stephen Shore chromogenic colour prints from 1976 where the colours are still true and have not faded. This was incredible – seeing vintage prints from one of the early masters of colour photography; noticing that they are not full of contrast like a lot of today’s colour photographs – more like a subtle Panavision or Technicolor film from the early 1960s. Rich, subtle, beautiful hues. For a contemporary colour photographer the trip to Bendigo just to see these two prints would be worth the time and the car trip/rail ticket alone!

.

Not everything is sweetness and light. The print by Dorothea Lange Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California is a contemporary print from 2003, the vintage print having just been out on loan; the contemporary section, The contemporary narrative, is very light on, due mainly to the nature of the holdings of George Eastman House; and there are some major photographers missing from the line up including Minor White, Fredrick Sommer, Paul Caponigro, Wynn Bullock and William Clift to name just a few.

Of more concern are the reproductions in the catalogue, the images for reproduction supplied by George Eastman House and the catalogue signed off by them. The reproduction of Margaret Bourke-White’s Chrysler Building (1930, see below) bears no relationship to the print in the exhibition and really is a denigration to the work of that wonderful photographer. Other reproductions are massively oversized, including the Alfred Stieglitz Equivalent, Lewis Hine’s Powerhouse mechanic (see below) and Tina Modotti’s Woman Carrying Child (c.1929). In Walter Benjamin’s terms (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction) the aura of the original has been lost and these reproductions further erode the authenticity of the original in their infinite reproducability. Conversely, it could be argued that the reproduction auraticizes the original:

“The original artwork has become a device to sell its multiply-reproduced derivatives; reroductability turned into a ploy to auraticize the original after the decay of aura…”3

In other words, after having seen so many reproductions when you actually see the original – it is like a bolt of lightning, the aura that emanates from the original. This is so true of this exhibition but it still begs the question: why reproduce in the catalogue at a totally inappropriate size? Personally, I believe that the signification of the reproduction (in terms of size and intensity of visualisation) is so widely at variance with the original one must question the decision to reproduce at this size knowing that this variance is a misrepresentation of the artistic interpretation of the author.

.

In conclusion, this is a sublime exhibition well worthy of the time and energy to journey up to Bendigo to see it. A true lover of classical American black and white and colour photography would be a fool to miss it!

Marcus Bunyan for the Art Blart blog

.

.

Actual size of print: 9.2 x 11.8 cm

Size of print in catalogue: 18.5 x 13.9 cm

These two photographs represent a proportionate relation between the two sizes as they appear in print and catalogue but because of monitor resolutions are not the actual size of the two prints.

.

.

Alfred Stieglitz

Equivalent

1923

gelatin silver print

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

Actual size of print: 16.9 x 11.8 cm

Size of print in catalogue: 23.2 x 15.8 cm

These two photographs represent a proportionate relation between the two sizes as they appear in print and catalogue but because of monitor resolutions are not the actual size of the two prints.

.

.

Lewis Hine

[Powerhouse mechanic]

1920

gelatin silver print

Transfer from the Photo League Lewis Hine Memorial Committee, ex-collection Corydon Hine

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

As it approximately appears in the exhibition (above, from my notes, memory and comparing the print in the exhibition with the catalogue reproduction)

Below, as the reproduction appears in the catalogue (scanned)

.

.

Margaret Bourke-White

Chrysler Building

New York City

1930

Silver gelatin photograph

.

.

“An exhibition of treasures from arguably the world’s most important photographic museum, George Eastman House, has been developed by Bendigo Art Gallery. The exhibition American Dreams will bring, for the first time, eighty of some of the most iconic photographic images from the 20th Century to Australia.

The choice of works highlights the trailblazing role these American artists had on the world stage in developing and shaping the medium, and the impact these widely published images had on the greater community.

Curator Tansy Curtin, who worked closely with George Eastman House developing the exhibition commented, “Through these images we can recognise the extraordinary ability of these artists, and their pivotal role influencing the evolution of photography. Their far-reaching images helped shape American culture, and impacted on the fundamental role photography has in communications today. Even more than this we can see through these artists the burgeoning love of photography that engaged a nation.”

Through these images we can see not only the development of photography, but also as some of the most powerful social documentary photography of last century, we see extraordinary moments captured in the lives of a wide range of Americans. The works distil the dramatic transformation that affected people during the 20th century – the affluence, degradation, loss, hope and change – both personally and throughout society.

The role of photography in nation building is exemplified in Ansel Adams’ majestic portraits of Yosemite national park, Bourke-White’s Chrysler building and images of migrants and farm workers during the Depression. Tansy Curtin added, “We see the United States ‘growing up’ through photography. We see hopes raised and crushed and the inevitable striving for the American Dream.” Director of Bendigo Art Gallery Karen Quinlan said, “We are thrilled to have been given this unprecedented opportunity to work with this unrivalled photographic archive. The resulting exhibition ‘American Dreams’, represents one of the most important and comprehensive collections of American 20th Century photography to come to Australia.”

George Eastman House holds over 400,000 images from the invention of photography to the present day. George Eastman, one time owner of the home in which the archives are housed, founded Kodak and revolutionised and democratised photography around the world. Eastman is considered the grandfather of snapshot photography.

American Dreams is one of the first exhibitions from this important collection to have been curated by an outside institution. It will be the first time Australian audiences have been given the opportunity to engage with this vast archive.”

Press release from the Bendigo Art Gallery

.

.

Alfred Steiglitz

[Georgia O'Keefe hand on back tire of Ford V8]

1933

gelatin silver print

Part purchase and part gift from Georgia O’Keefe

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

Walker Evans

Torn Poster, Truro, Massachusetts

1930

gelatin silver contact print

Purchased with funds from National Endowment for the Arts

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

Dorothea Lange

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

1936, printed c2003

photogravure print

Gift of Sean Corcoran

Collection of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

.

.

1. Anon. “Zone System,” on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 13/06/2011

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_System

2. Anon. “Equivalents,” on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 13/06/2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equivalents

3. Huyssen, Andreas. Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. London: Routledge, 1995, pp. 23-24.

.

.

Bendigo Art Gallery

42 View Street Bendigo

Victoria Australia 3550

T: 03 5434 6088

General admission fees for this exhibition

Adults - $12

Concession/tertiary - $10

Primary/secondary - $4

Opening hours:

Bendigo Art Gallery is open daily 10am to 5pm

Filed under: american photographers, beauty, black and white photography, Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus, documentary photography, Edward S. Curtis, Edward Steichen, exhibition, existence, gallery website, landscape, light, memory, New York, photographic series, photography, photojournalism, pictorialism, portrait, psychological, reality, space, street photography, surrealism, time, Walker Evans Tagged: 20th century photography, Alfred Steiglitz Georgia O'Keefe hand on back tire of Ford V8, Alfred Stieglitz, Alfred Stieglitz Equivalent, American Dreams: 20th century photography from George Eastman House, Bendigo, Bendigo Art Gallery, Chrysler Building, dorothea lange, Dorothea Lange Kern County California, Dorothea Lange Migrant Mother, equivalent, George Eastman, george eastman house, Georgia O'Keefe, Georgia O'Keefe hand on back tire of Ford V8, Gertrude Käsebier, Gertrude Käsebier The Sketch (Beatrice Baxter), International Museum of Photography and Film, Kern County California, Lewis Hine, Lewis Hine Powerhouse mechanic, Margaret Bourke-White, Margaret Bourke-White Chrysler Building, Migrant Mother Nipomo California, Powerhouse mechanic, Tansy Curtin, the city, The Sketch (Beatrice Baxter), Torn Poster Truro, Walker Evans, Walker Evans Torn Poster Truro, war photography, Wegee

Review: ‘Selina Ou: New York’ at Sophie Gannon Gallery, Richmond

Exhibition dates: 25th October – 19th November 2011

.

A strong, nuanced body of work by Selina Au at Sophie Gannon Gallery in Richmond. In the flesh these large colour photographs have a wonderful, polyvocal presence. The solo portraits are stronger in terms of composition and intertextuality than the double portraits.

Derived from the Latin intertexto, meaning to intermingle while weaving, intertextuality is a term first introduced by French semiotician Julia Kristeva in the late sixties.1 Intertextuality “is always an iteration which is also a re-iteration, a re-writing which foregrounds the trace of the various texts it both knowingly and unknowingly places and dis-places.”2 Intertexuality is how a text is constituted. It fragments singular readings. The reader’s own previous readings, experiences and position within the cultural formation influences these re-inscriptions.

Reminding me of a contemporary redefinition of the work of Diane Arbus, Ou’s reconceptualisations of space “produce a plurality of meanings and signifying/interpretive gestures that escape the reduction of knowledge to fixed, monological re-presentations, or presences.”3 Through a process of materialisation, using the technique of assemblage, Ou weaves a lack of fixity into her photographs. She creates a kind of tapestry in the surfaces of her images, a play of pattern/randomness that redefines the significations of the body in the fold of inscription.

Take the first three portraits in this posting, for example. The photograph Tim, Hair Stylist, Lower East Side, New York weaves space, time and memory within the pictorial frame. The physical space between the portrait on the wall at rear, Tim and the clock at right is crucial to a reading of this photograph, as is the disjuncture between the appearance of the man in the framed photograph (in jacket and tie) and the casual attire of Tim. Just as important is the memorialisation of both men within the same space (where both presumably work/ed), the collapsing of past and present into a fluid space that is neither here nor there (the past of the man in the framed photograph, the moment of passing of Tim when the photograph was ‘taken’ and the present of the photograph being looked at). There is no fixed, monological representation here: the reading of this photograph hovers between past and present, between memory and reality and haunts the body of the subject, Tim.

Similarly, Raquel, Waitress and Fashion Designer, Nolita, New York and Jerome, Retail Assistant and Fashion Designer, Soho, New York offer radical re-iterations of space, this time with less temporal associations. In Raquel, two red chevrons at top left and right frame the face of the subject, playing off the colour-changing hair of the waitress/fashion designer, the title of the photograph an ironic comment on the intertextual nature of contemporary life: a waitress (low paid, menial labourer) and a fashion designer (famous, highly visible entrepreneur). The nonchalantly limp-wristed, ringed hand and over large glasses, coupled with the bedraggled threads of the black shorts – echoing the tousled nature of the subjects hair – also belies the statement “fashion designer.” The word Cervesas (beer) offers a dichotomy with the coloured bottles of flavoured water that surround the lower half of the subject while the reflection in the window behind Raquel provides a metaphorical vista into this distorted world view.

In Jerome, the same problem in a person’s relationship with self and others is evident: the context of Jerome as both a retail assistant (low paid, menial labourer) and a fashion designer (famous, highly visible entrepreneur). The narcissistic, self-importance of Jerome is beautifully portrayed by Ou as she balances the context of his body in space – his polka-dot shirt reflecting the dotted neon of the shops name, his logo emblazoned necklace doing the same, while the reflections in the shop window again hint at outside forces (the car and consumerism) and other worlds. The defiant, could not give a shit gaze of the subject into the camera lens hints at years of subjugation and unrequited ambition for this is not his shop, these are not his clothes despite the label “fashion designer.” He is just a retail assistant, the subject of his own con(text).

The strength of these photographs is that they blur the outlines of the fixed image dispersing an image of totality, “into an unbounded, illimitable tissue of connections and associations, paraphrases and fragments, texts and con-texts.”4 In this sense the solo portraits are much more successful than the rest of the work as Ou magically weaves the tapestry of life into her compositions, ready for the reader to bring their own experiences to these re-inscriptions. In a word these photographs are, literally, breath-taking.

.

Many thankx to Sophie Gannon Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

.

.

.

Selina Ou

Tim, Hair Stylist, Lower East Side, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

Selina Ou

Raquel, Waitress and Fashion Designer, Nolita, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

Selina Ou

Jerome, Retail Assistant and Fashion Designer, Soho, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

Selina Ou

Darren, Model and Carlito, Artist, Soho, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

Selina Ou

Carolyn and Jane, Lolitas, Brooklyn Botanical Garden, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

Selina Ou

Issa and Lamine, Taxi Mechanics, Upper West Side, New York

2011

C-type print

100 x 100cm

.

.

1. Keep, Christopher, McLaughlin, Tim and Parmar, Robin. “Interxtuality,” on The Electronic Labyrinth website [Online] Cited 13/11/2011. elab.eserver.org/hfl0278.html

2. Ibid.,

3. Thumlert, Kurt. Intervisuality, Visual Culture, and Education. [Online] Cited 10/08/2006.

www.forkbeds.com/visual-pedagogy.htm (no longer available)

4. Keep Op cit.,

.

.

Sophie Gannon Gallery

2, Albert Street

Richmond, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Tues – Saturday 11 – 5pm

Filed under: Australian artist, colour photography, Diane Arbus, digital photography, documentary photography, exhibition, existence, gallery website, Melbourne, New York, photographic series, photography, portrait, space, time Tagged: Brooklyn Botanical Garden, Darren Model and Carlito Artist, Issa and Lamine Taxi Mechanics, Jerome Retail Assistant and Fashion Designer, Lolitas, New York City, Raquel Waitress and Fashion Designer, Richmond, Selina Ou Carolyn and Jane, Selina Ou Darren Model and Carlito Artist, Selina Ou Issa and Lamine Taxi Mechanics, Selina Ou Jerome Retail Assistant and Fashion Designer, Selina Ou Raquel Waitress and Fashion Designer, Selina Ou Tim Hair Stylist Lower East Side, Selina Ou: New York, Soho, Sophie Gannon Gallery, the city, Tim Hair Stylist Lower East Side, Upper West Side

melbourne’s magnificent nine 2011

.

Here’s my pick of the nine best exhibitions in Melbourne (with excursions to Bendigo and Hobart thrown in) that appeared on the Art Blart blog in 2011. Enjoy!

Marcus

.

.

1/ Sidney Nolan: Drought Photographs at Australian Galleries, Melbourne, March 2011

.

.

Sidney Nolan

Untitled (calf carcass in tree)

1952

archival inkjet print

23.0 cm x 23.0 cm

.

.

This was a superb exhibition of 61 black and white photographs by Sidney Nolan. The photographs were shot using a medium format camera and are printed in square format from the original 1952 negatives.

The work itself was a joy to behold. The photographs hung together like a symphony, rising and falling, with shape emphasising aspects of form. The images flowed from one to another. The formal composition of the mummified carcasses was exemplary, the resurrected animals (a horse, for example, propped up on a fifth leg) and emaciated corpses like contemporary sculpture. The handling of the tenuous aspects of human existence in this uniquely Australian landscape wass also a joy to behold. Through an intimate understanding of how to tension the space between objects within the frame Nolan’s seemingly simple but complex photographs of the landscape are previsualised by the artist in the mind’s eye before he even puts the camera to his face.

.

2/ Bill Henson at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, March – April 2011

This was an exquisite exhibition by one of Australia’s preeminent artists. Like Glenn Gould playing a Bach fugue, Bill Henson is grand master in the performance of narrative, structure, composition, light and atmosphere. The exhibition featured thirteen large colour photographs printed on lustre paper (twelve horizontal and one vertical) – nine figurative of adolescent females, two of crowd scenes in front of Rembrandt paintings in The Hermitage, St. Petersburg (including the stunning photograph that features ‘The return of the prodigal son’ c. 1662 in the background, see below) and two landscapes taken off the coast of Italy. What a journey this exhibition took you on!

Henson’s photographs have been said by many to be haunting but his images are more haunted than haunting. There is an indescribable element to them (be it the pain of personal suffering, the longing for release, the yearning for lost youth or an understanding of the deprecations of age), a mesmeric quality that is not easily forgotten. The photographs form a kind of afterimage that burns into your consciousness long after the exposure to the original image has ceased. Haunted or haunting they are unforgettable.

.

.

Bill Henson

Untitled

2009/10

CL SH767 N17B

Archival inkjet pigment print

127 x 180 cm

Edition of 5

.

3/ Networks (cells & silos) at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), Caulfield, February – April 2011

This was a vibrant and eclectic exhibition at MUMA, one of the best this year in Melbourne. The curator Geraldine Barlow gathered together some impressive, engaging works that were set off to good effect in the new gallery spaces. I spent a long and happy time wandering around the exhibition and came away visually satiated and intellectually stimulated. The exhibition explored “the connections between artistic representation of networks; patterns and structures found in nature; and the rapidly evolving field of network science, communications and human relations.”

.

.

Installation photograph of one of the galleries in the exhibition NETWORKS (cells & silos) at the newly opened Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) with Nick Mangan’s Colony (2005) in the foreground

.

4/ Monika Tichacek, To all my relations at Karen Woodbury Gallery, Richmond, May 2011

This was a stupendous exhibition by Monika Tichacek, at Karen Woodbury Gallery. One of the highlights of the year, this was a definite must see!

The work was glorious in it’s detail, a sensual and visual delight (make sure you click on the photographs to see the close up of the work!). The riotous, bacchanalian density of the work was balanced by a lyrical intimacy, the work exploring the life cycle and our relationship to the world in gouache, pencil & watercolour. Tichacek’s vibrant pink birds, small bugs, flowers and leaves have absolutely delicious colours. The layered and overlaid compositions show complete control by the artist: mottled, blotted, bark-like wings of butterflies meld into trees in a delicate metamorphosis; insects are blurred becoming one with the structure of flowers in a controlled effusion of life.

.

.

Monika Tichacek

To all my relations (detail)

2011

.

5/ American Dreams: 20th century photography from George Eastman House at Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria, April – July 2011

.

.

Diane Arbus

Untitled (6)

1971

.

.

This was a fabulous survey exhibition of the great artists of 20th century American photography, a rare chance in Australia to see such a large selection of vintage prints from some of the masters of photography. If you had a real interest in the history of photography then you hopefully saw this exhibition, showing as it is just a short hour and a half drive (or train ride) from Melbourne at Bendigo Art Gallery.

.

6/ Time Machine: Sue Ford at Monash Gallery of Art, Wheelers Hill, Victoria, April – June 2011

.

.

Sue Ford (1943–2009)

Self-portrait 1976

1976

from the series Self-portrait with camera (1960–2006)

selenium toned gelatin silver print, printed 2011

24 x 18 cm

courtesy Sue Ford Archive

.

.

This beautifully hung exhibition flowed like music, interweaving up and down, the photographs framed in thin, black wood frames. It featured examples of Ford’s black and white fashion and street photography; a selection of work from the famous black and white Time series (being bought for their collection by the Art Gallery of New South Wales); a selection of Photographs of Women - modern prints from the Sue Ford archive that are wonderfully composed photographs with deep blacks that portray strong, independent, vulnerable, joyous women (see last four photographs below); and the most interesting work in the exhibition, the posthumous new series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006) that evidence, through a 47 part investigation using colour prints from Polaroids, silver gelatin prints printed by the artist, prints made from original negatives and prints from scanned images where there was no negative available, a self-portrait of the artist in the process of ageing.

Whether looking down, looking toward or looking inward these fantastic photographs show a strong, independent women with a vital mind, an élan vital, a critical self-organisation and an understanding of the morphogenesis of things that will engage us for years to come. Essential looking.

.

7/ The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), Hobart, August 2011

My analogy: you are standing in the half-dark, your chest open, squeezing the beating heart with blood coursing between your fingers while the other hand is up your backside playing with your prostrate gland. I think ringmeister David Walsh would approve. My best friends analogy: a cross between a car park, night club, sex sauna and art gallery.

Weeks later I am still thinking about the wonderful immersive, sensory experience that is MONA. Peter Timms in an insightful article in Meanjin calls it a post-Google Wunderkammer, or wonder chest. It can be seen as a mirabilia – a non-historic installation designed primarily to delight, surprise and in this case shock. The body, sex, death and mortality are hot topics in the cultural arena and Walsh’s collection covers all bases. The collection and its display are variously hedonistic, voyeuristic, narcissistic, fetishistic pieces of theatre subsumed within the body of the spectacular museum architecture …

Spectatorship and their attendant erotics has MONA as a form of fetishistic cinema. It is as if what Barthes calls “the eroticism of place” were a modern equivalent of the eighteenth century genius loci, the “genius of the place.” The place is spectacular, the private collection writ large as public institution, the symbolic power of the institution masked through its edifice. The art become autonomous, cut free from its cultural associations, transnational, globalised, experienced through kinaesthetic means; the viewer meandering through the galleries, the anti-museum, as an international flaneur. Go. Experience!

.

.

Corten Stairwell & Surrounding Artworks

February 2011

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

.

8/ John Bodin: Rite of Passage at Anita Traverso Gallery, Richmond, August – September 2011

.

.

John Bodin

I Was Far Away From Home

2009

Type C print on metallic paper

80 x 110cm

.

.

The photographs become the surface of the body, stitched together with lines, markers pointing the way – they are encounters with the things that we see before us but also the things that we carry inside of us. It is the interchange between these two things, how one modulates and informs the other. It is this engagement that holds our attention: the dappled light, ambiguity, unevenness, the winding path that floats and bobs before our eyes looking back at us, as we observe and are observed by the body of these landscapes.

One of the fundamental qualities of the photographs is that they escape our attempts to rationalize them and make them part of our understanding of the world, to quantify our existence in terms of materiality. I have an intimate feeling with regard to these sites of engagement. They are both once familiar and unfamiliar to us; they possess a sense of nowhereness. A sense of groundlessness and groundedness. A collapsing of near and far, looking down, looking along, a collapsing of the constructed world.

Like the road in these photographs there is no self just an infinite time that has no beginning and no end. The time before my birth, the time after my death. We are just in the world, just being somewhere. Life is just a temporary structure on the road from order to disorder. “The road is life,” writes Jack Kerouac in On the Road.

.

9/ Juan Davila: The Moral Meaning of Wilderness at the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), Caulfield, August – October 2011

Simply put, this was one of the best exhibitions I saw in Melbourne this year.

I had a spiritual experience with this work for the paintings promote in the human a state of grace. The non-material, the unconceptualizable, things which are outside all possibility of time and space are made visible. This happens very rarely but when it does you remember, eternally, the time and space of occurrence. I hope you had the same experience.

.

.

Juan Davila

Wilderness

2010

© Juan Davila, Courtesy Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art

.

10/ In camera and in public at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, September – October 2011

.

.

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Untitled

1971

From the series The Park

Gelatin Silver Print

© Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

.

.

Curated by Naomi Cass as part of the Melbourne Festival, this was a brilliant exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne. The exhibition explored, “the fraught relationship between the camera and the subject: where the image is stolen, candid or where the unspoken contract between photographer and subject is broken in some way – sometimes to make art, sometimes to do something malevolent.” It examined the promiscuity of gazes in public/private space specifically looking at surveillance, voyeurism, desire, scopophilia, secret photography and self-reflexivity. It investigated the camera and its moral and physical relationship to the unsuspecting subject.

.

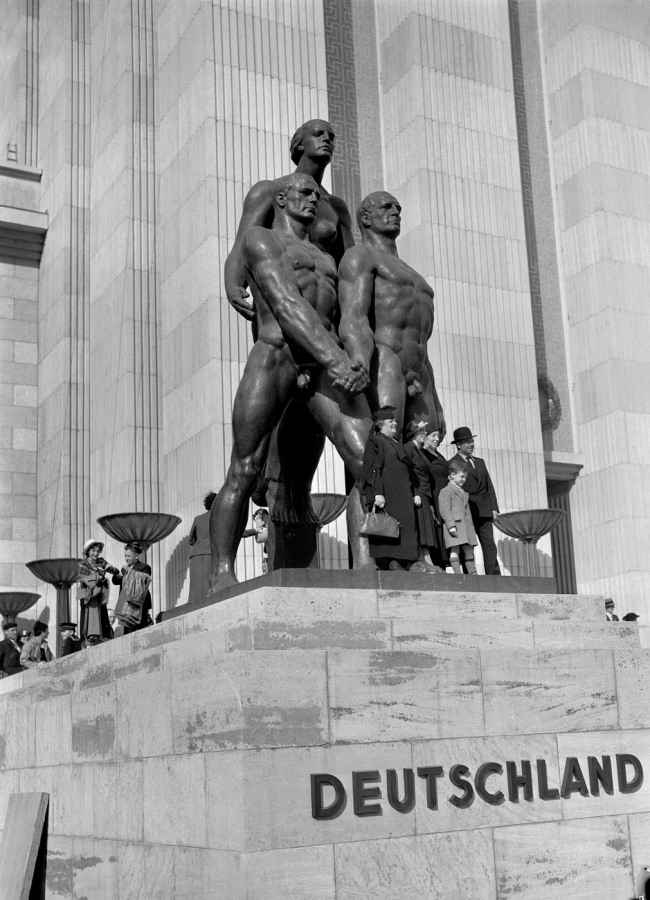

11/ The Mad Square: Modernity in German Art 1910 – 37 at The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, November 2011 – March 2012

This is one of the best exhibitions this year in Melbourne bar none. Edgy and eclectic the work resonates with the viewer in these days of uncertainty: THIS should have been the Winter Masterpieces exhibition!

The title of the exhibition, The mad square (Der tolle Platz) is taken from Felix Nussbaum’s 1931 painting of the same name where “the ‘mad square’ is both a physical place – the city, represented in so many works in the exhibition, and a reference to the state of turbulence and tension that characterises the period.” The exhibition showcases how artists responded to modern life in Germany in the interwar years, years that were full of murder and mayhem, putsch, revolution, rampant inflation, starvation, the Great Depression and the rise of National Socialism. Portrayed is the dystopian, dark side of modernity (where people are the victims of a morally bankrupt society) as opposed to the utopian avant-garde (the prosperous, the wealthy), where new alliances emerge between art and politics, technology and the mass media. Featuring furniture, decorative arts, painting, sculpture, collage and photography in the sections World War 1 and the Revolution, Dada, Bauhaus, Constructivism and the Machine Aesthetic, Metropolis, New Objectivity and Power and Degenerate Art, it is the collages and photographs that are the strongest elements of the exhibition, particularly the photographs. What a joy they are to see.

.

.

Albert Renger-Patzsch

Harbour with crane

c.1927

gelatin silver photograph

printed image 22.7 h x 16.8 w cm

Purchased 1983

.

.

Filed under: American, american photographers, Ansel Adams, Art Blart, Australian artist, Australian writing, beauty, black and white photography, Diane Arbus, digital photography, documentary photography, exhibition, existence, gallery website, landscape, light, Marcus Bunyan, Melbourne, memory, National Gallery of Victoria, photographic series, photography, portrait, review, space, time Tagged: Albert Renger-Patzsch Harbour with crane, Anita Traverso Gallery, Australian Galleries, Bendigo, Bendigo Art Gallery, Bill Henson, Bill Henson Untitled 2009/10, CCP, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Corten Stairwell, Diane Arbus, Diane Arbus Untitled (6), Hobart, I Was Far Away From Home, In camera and in public, John Bodin I Was Far Away From Home, John Bodin: Rite of Passage, Juan Davila, Juan Davila Wilderness, Juan Davila: The Moral Meaning of Wilderness, karen woodbury gallery, Kohei Yoshiyuki Untitled, MONA, Monash Gallery of Art, Monash University Museum of Art, Monika Tichacek, Monika Tichacek To all my relations, MUMA, Museum of Old and New Art, NETWORKS (cells & silos), Richmond, Self-portrait with camera, Sidney Nolan, Sidney Nolan Drought Photographs, Sidney Nolan Untitled (calf carcass in tree), Sue Ford, Sue Ford Self-portrait 1976, Sue Ford Self-portrait with camera, The Mad Square: Modernity in German Art 1910 - 37, The Moral Meaning of Wilderness, Time Machine: Sue Ford, To all my relations, Tolarno Galleries, Victoria

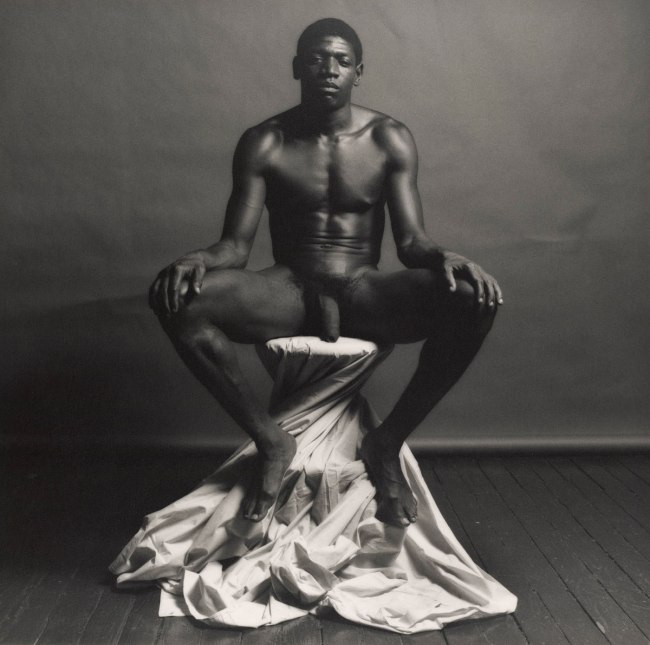

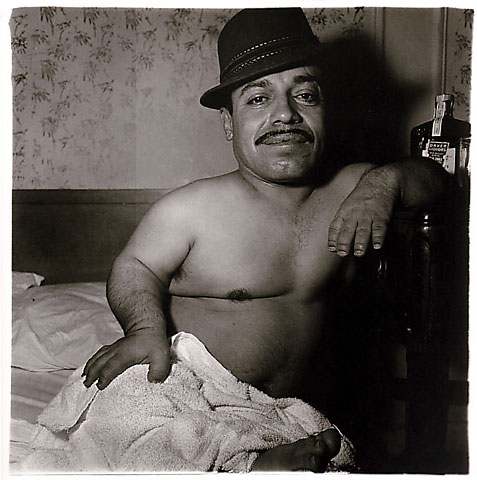

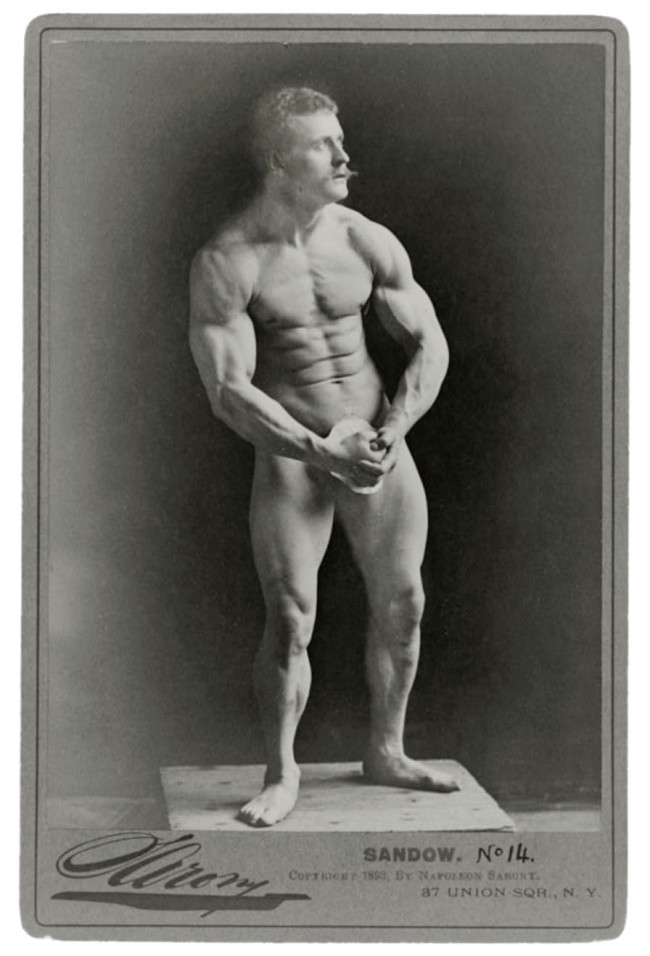

Exhibition: ‘Naked Before the Camera’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Exhibition dates: 27th March – 9th September 2012

.

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

.

.

.

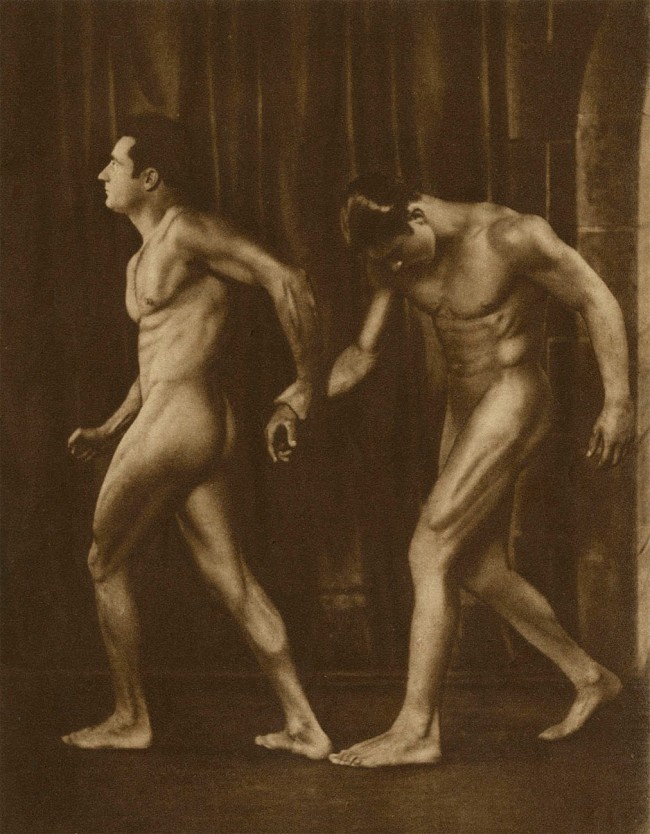

Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 – after 1900)

Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]

1856-59

Salted paper print from glass negative

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1998

.

.

Eugène Durieu (French, 1800 – 1874)

Untitled [Seated Female Nude]

1853-54

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis Gift, 2005

.

.

Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 – after 1867)

Untitled [Standing Male Nude]

ca. 1855

Salted paper print from paper negative

Purchase, Ezra Mack Gift and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991

.

.

Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 – after 1875)

Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]

ca. 1850

Daguerreotype

The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Anonymous Gift and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997

.

.

“Depicting the human body has been among the greatest challenges, preoccupations, and supreme achievements of artists for centuries. The nude – even in generalized or idealized renderings – has triggered impassioned discussions about sin, sexuality, cultural identity, and canons of beauty, especially when the chosen medium is photography, with its inherent accuracy and specificity. Through September 9, 2012, Naked before the Camera, an exhibition of more than 60 photographs selected from the renowned holdings of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, surveys the history of this subject and explores some of the motivations and meanings that underlie photographers’ fascination with the nude.

“In every culture and across time, artists have been captivated by the human figure,” commented Thomas P. Campbell, Director of the Metropolitan. “In ‘Naked before the Camera’, we see how photographers have used their medium to explore this age-old subject and create compelling new images.”

The exhibition begins in the 19th century, when photographs often served artists as substitutes for live models. Such “studies for artists” were known to have been used by the French painter Gustave Courbet, whose Woman with a Parrot (1866), for instance, is strikingly similar to photographer Julien Vallou de Villeneuve’s Female Nude of 1853. Even when their stated purpose was to aid artists, however, the best of these 19th-century photographs of the nude were also intended as works of art in their own right. Two recently acquired photographs, made in the mid-1850s by an unknown French artist, are striking examples. Not only are they larger than all other photographic nudes from the time, they stand out due to an extraordinary surface pattern that interrupts the images and suggests a view through gossamer or a photograph printed on finely pleated silk rather than paper. The elegant Female Nude harkens back to an Eve or Venus and is vignetted by the camera lens as if seen through a peephole, while her male counterpart is shown in strict profile in a pose that recalls precedents from antiquity. Each figure draws from the past while being presented in a strikingly modern way, without any equivalent among other 19th-century studies for artists.

Not all photographers of the nude were motivated by artistic desire. The second section of Naked before the Camera includes photographs made for medical and forensic purposes, as ethnographic studies, as tools to analyze anatomy and movement, and – not surprisingly – as erotica. The lines between such categories were not always clearly drawn; some photographers called their images “studies for artists” merely to evade the censors, while viewers of the G. W. Wilson Studio’s Zulu Girls (1892-93) or Paul Wirz’s ethnographic photographs of scantily clad Indonesians from the 1910s and 1920s were undoubtedly titillated by the blending of exoticism and eroticism.

Beginning in the fertile period of modernist experimentation that followed on the heels of World War I, photographers such as Brassaï, Man Ray, Hans Bellmer, André Kertész, and Bill Brandt found in the human body a perfect vehicle for both visual play and psycho-sexual exploration. In Distortion #6 (1932) by André Kertész, a woman’s body is stretched and pulled in the reflections of a fun-house mirror – a figure from a Surrealist dream that stands in stark contrast to the images of perfect feminine beauty by earlier photographers.

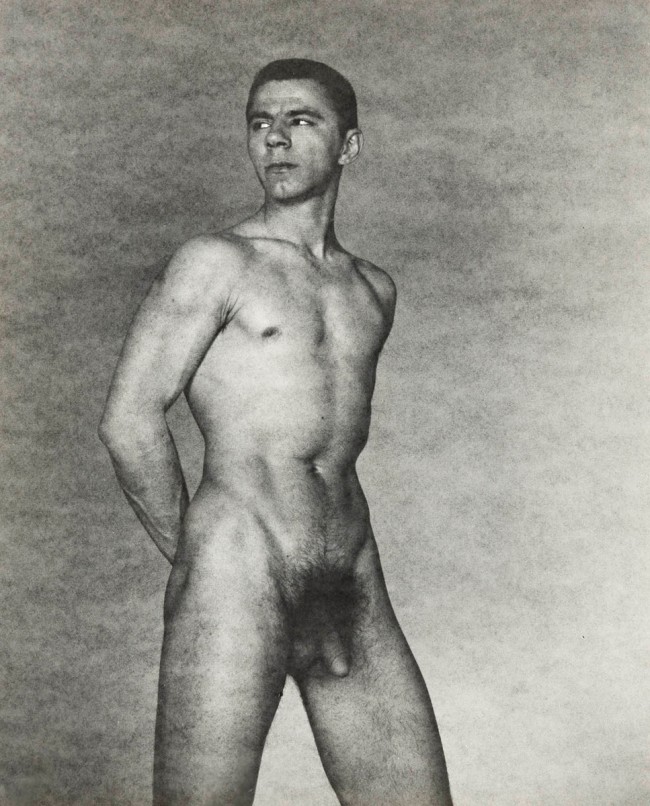

In mid-20th-century America, photographers more often communicated an intimate connection with their subjects. Following the example of Alfred Stieglitz’s famed portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, photographers such as Edward Weston, Harry Callahan, and Emmet Gowin made many nude studies of their wives. Callahan’s photograph of his wife and daughter, Eleanor and Barbara, Chicago (1954), for instance, gives the viewer access to a private, tender moment of intimacy.

In the wake of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the AIDS crisis that began in the 1980s, artists began to think of the body as a politicized terrain and explored issues of identity, sexuality, and gender. Diane Arbus’s Retired man and his wife at home in a nudist camp one morning, N.J. (1963) and A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. (1968), Larry Clark’s untitled image (1972-73) from the series Teenage Lust, and Hannah Wilke’s Snatch Shot with Ray Gun (1978) are among the works featured in the concluding section of the exhibition.”

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

.

.

Brassaï (French (born Romania), Brasov 1899 – 1984 Côte d’Azur)

Nude

1931-34

Gelatin silver print

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2007

© The Estate of Brassai

.

.

Man Ray (American, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1890 – 1976 Paris)

Arm

ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2012 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

.

.

André Kertész (American (born Hungary), Budapest 1894–1985 New York City)

Distortion #6

1932

Gelatin silver print

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© The Estate of André Kertész / Higher Pictures

.

.

Irving Penn (American, Plainfield, New Jersey 1917 – 2009 New York City)

Nude No. 57

1949 – 50

Gelatin silver print

Gift of the artist, 2002

© 1950-2002 Irving Penn

.

.

Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959 – 1989)

Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]

ca. 1987

Gelatin silver print

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2009

© The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur

.

.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

T: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Thursday: 9:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m.*

Friday and Saturday: 9:30 a.m. – 9:00 p.m.*

Sunday: 9:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m.*

Closed Monday (except Met Holiday Mondays**), Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day

The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Filed under: American, american photographers, beauty, black and white photography, Diane Arbus, documentary photography, English artist, exhibition, existence, gallery website, memory, photographic series, photography, portrait, psychological, reality, sculpture, space, time Tagged: Albumen silver print, André Kertész Distortion #6, Andre Kertesz, Brassaï Nude, Brassai, camera, Charles Alphonse Marlé, Charles Alphonse Marlé Standing Male Nude, Chauvassaignes Female Nude in Studio, daguerreotype, Distortion #6, early photographic processes, Eugène Durieu Seated Female Nude, eugene durieu, Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin, female nude, Female Nude in Studio, Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes, French photographers, French photography, gelatin silver print, glass negative, Irving Penn, Irving Penn Nude No. 57, male nude, Man Ray, Man Ray Arm, Mark Morrisroe, Mark Morrisroe Two Men in Silhouette, Marlé Standing Male Nude, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Moulin Two Standing Female Nudes, naked, Naked Before the Camera, paper negative, photography and the body, photography and the nude, Salted paper print, surrealism, the body, Two Men in Silhouette, Two Standing Female Nudes

Exhibition: ‘True Stories: American Photography from the Sammlung Moderne Kunst’ at Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Exhibition dates: 2nd March – 20th September 2012

.

You can’t get much better than this to start a posting: Baltz, Friedlander, Winogrand, Nixon, Baldessari, Eggleston and Shore. I recall seeing my first vintage Stephen Shore at the American Dreams exhibition at the Bendigo Art Gallery last year. What a revelation. At the time I said,

“Two Stephen Shore chromogenic colour prints from 1976 where the colours are still true and have not faded. This was incredible – seeing vintage prints from one of the early masters of colour photography; noticing that they are not full of contrast like a lot of today’s colour photographs – more like a subtle Panavision or Technicolor film from the early 1960s. Rich, subtle, beautiful hues.”

You can get an idea of those colours in the image posted here. Like an early Panavision or Technicolor feature film.

Perhaps there is something to this analogue photography that digital will never be able to capture, let alone reproduce…

.

Many thankx to Pinakothek der Moderne for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

.

.

.

Lewis Baltz (*1945)

Greenbrae

1968

from the series The Prototype Works

Vintage gelatin silver print

13.1 x 21.4 cm

Sammlung Moderne Kunst in the Pinakothek der Moderne Munich, Acquired in 2011 by PIN. Freunde der Pinakothek der Moderne e.V.

© Lewis Baltz

.

.

Lee Friedlander (*1934)

Route 9W, New York

1969

Gelatin silver print, Baryt paper (card)

20.4 x 30.5 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Lee Friedlander

.

.

Garry Winogrand (1928-1984)

Los Angeles, California

1969

Gelatin silver print (pre 1984)

21.8 x 32.8 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Estate of Garry Winogrand

.

.

Nicholas Nixon (*1947)

View of State Street, Boston

1976

from the series Boston Views 1974 – 1976

Gelatin silver print, Baryt paper (card)

20.3 x 25.2 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Nicholas Nixon

.

.

John Baldessari (*1931)

Man Running/Men Carrying Box

1988 – 1990

Gelatin silver prints, vinyl paint and shading in oil

Part 1: 121.3 x 118.6 cm; Part 2: 121.3 x 146.6 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© John Baldessari

.

.

William Eggleston (*1939)

Untitled

1980

The first of 15 works from the portfolio Troubled Waters

Dye transfer print

29.0 x 44.0 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

.

.

Stephen Shore (*1947)

La Brea Avenue & Beverly Boulevard, Los Angeles, California

1975

Chromogenic print, Kodak professional paper (1998)

20.4 x 25.5 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Stephen Shore

.

.

“American photography forms an extensive and simultaneously top-quality focal point in the collection, of which a selected overview is now being exhibited for the first time. The main interest of young photographers, who have been examining changes in political, social and ecological aspects of everyday American life since the late 1960s, has been the American social landscape. They have developed new pictorial styles that define stylistic devices perceived as genuinely American while at the same time being internationally recognised. Whereas Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz and Larry Clark, who are now considered classical modern photographers, have remained true to black-and-white photography, William Eggleston and Stephen Shore in particular have established colour photography as an artistically independent form of expression. The exhibition brings together around 100 works that, thanks to the Siemens Photography Collection and through acquisitions, bequests and donations, are now part of the museum’s holdings. True stories covers a spectrum from the street photography of the late 1960s to New Topographics and pictures by the New York photographer Zoe Leonard, taken just a few years ago.

“A new generation of photographers has directed the documentary approach toward more personal ends. Their work betrays a sympathy for the imperfection and frailties of society. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it.” With the exhibition New Documents in spring 1967, John Szarkowski, the influential curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, rang in a new era in American photography. Those photographers represented, including Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand in addition to Diane Arbus, stood for a change in attitude within documentary photography that was conditioned exclusively by the subjective viewpoint of an individual’s reality. The object of photographic interest lay in the American social landscape and its conditions. It was less concerned with the natural landscape and its increasingly cultural reshaping than with the urban or urbanised space and how people move within it. In so doing, the New Documentarians rejected any obviously explanatory impetus, turning instead to the everyday and commonplace.

The exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape that was staged in the mid 1970s at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, represented a countermovement to this subjective form of expression. Their protagonists, including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Nicholas Nixon and Stephen Shore, also pleaded for a documentary approach and were influenced by figures such as Walker Evans und Robert Frank, but considered themselves rooted in the tradition of 19th-century topographical photography in particular. The prime initiator of this working method, that was expressly not governed by style, is the Los Angeles-based artist Ed Ruscha. Their central aim is a distanced and seemingly analytical depicition, free of judgement; their topic, the landscape altered by mankind. It is the image of the American West in particular, so much conditioned by myths and dreams but long since brought back to reality as a result of commercial and ecological exploitation, that is visible in their works.

The decisive quantum leap to establishing the position of colour photography was made by the Southerner William Eggleston in his exhibition in 1976, also held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the publication of the William Eggleston’s Guide. The harsh public criticism of his pictures was not to do with his use of colour but the fact that Eggleston photographed things and everyday situations – on the spur of the moment and in a seemingly careless manner – that, until then, had not been considered worthy of being photographed turning them into exquisite prints using the expensive and complicated dye-transfer process. In Eggleston’s cosmos of images that is strongly influenced by motifs and the light of the Mississippi Delta, colour constitutes the picture. The “rush of colour” championed by this exhibition led to the comprehensive implementation of colour photography in the field of artistic photography in the years that followed, starting in the USA and then in Europe – and especially in Germany.

An artistic attitude became established at the end of the 1970s that, with recourse to existing picture material from art, film, advertising and the mass media, formulated new pictorial concepts and, in the same breath, opened up traditional artistic and art-historical categories such as authorship, originality, uniqueness, intellectual property and authenticity to discussion. Appropriation Art owes its decisive influences to the artist John Baldessari, who lives and teaches in California. One of its most famous representatives is Richard Prince, who became famous in particular as a result of his artistic adaptation of advertising images. Concept art in the 1960s and ’70s similarly makes use of photography, both as part of an artistic practice using the most varied of materials and as a unique medium for documenting campaigns, happenings and performances. As works by Dan Graham and Zoe Leonard clearly show, the previously precisely delineated boundaries between photography that alludes to its own intrinsically, media-related history and the use of photography as an artistic strategy, have become more fluid.”

Press release from the Pinakothek der Moderne website

.

.

Dan Graham (*1942)

View Interior, New Highway Restaurant, Jersey City, N.J., (detail)

1967 (printed 1996)

C-prints

Each 50.6 x 76.2 cm

On permanent loan from Siemens AG, Munich, to the Sammlung Moderne Kunst since 2003

© Dan Graham

.

.

William Eggleston (*1939)

from Southern Suite (10-part series)

1981

Dye transfer print

25.0 x 38.2 cm

Sammlung Moderne Kunst in the Pinakothek der Moderne Munich. Acquired in 2006 through PIN. Freunde der Pinakothek der Moderne e.V.

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

.

.

Larry Clark (*1943)

Tulsa

1972